By Franck Essi, Senior Consultant, STRATEGIES !

The first article in this series highlighted a harsh reality: Africa loses between USD 60 and 90 billion each year due to illicit financial flows (IFFs). These losses exceed the official development assistance (ODA) received by the continent and weaken its economic sovereignty. But beyond the figures, an essential question remains: through which precise mechanisms do these funds escape?

This article examines the main mechanisms, the circuits they follow, and the structural challenges that allow IFFs to persist despite ongoing initiatives to curb them.

I. The Main Mechanisms of Illicit Financial Flows

Illicit financial flows rely on a complex architecture combining trade fraud, tax avoidance, criminal networks, corruption, and new technologies. Seven key mechanisms stand out.

1. Trade misinvoicing

Trade misinvoicing involves deliberately manipulating the declared values of imports and exports. Under-invoicing of exports transfers part of the revenue abroad, while over-invoicing of imports reduces taxable profits locally. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), this practice alone causes USD 30 to 52 billion in annual losses for Africa¹.

2. Transfer pricing and multinational tax avoidance

Multinational corporations often manipulate the prices of internal transactions – known as transfer pricing – to shift profits to subsidiaries in low-tax jurisdictions. This phenomenon, called Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS), is identified by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as one of the main causes of tax revenue losses in Africa².

3. Informal transfer systems

Flows also pass through parallel systems such as hawala. Hawala is a traditional trust-based remittance system, widespread in East Africa and the Sahel, where one agent accepts funds locally and instructs a partner agent in another country to pay the equivalent to the recipient. Transactions bypass banks and remain outside official oversight. In economies where the informal sector accounts for more than 40% of GDP, these networks are heavily used³.

4. Tax havens and shell companies

Tax havens play a central role by providing legal anonymity. They host billions through shell companies (entities created solely to obscure ownership) and trusts (legal structures masking the real beneficiaries of assets). The absence of reliable registries of beneficial ownership in many African states makes tracing almost impossible⁴.

5. The extractive sector and natural resources

Extractive industries – oil, gas, and mining – are particularly vulnerable to IFFs. Africa loses about USD 40 billion annually through opaque contracts, under-reported royalties, and intra-group price manipulations⁵. Illegal fishing and unregulated logging add to this hemorrhage.

6. Organized crime and corruption

Organized crime generates significant revenues from drug trafficking, smuggling of minerals and timber, and human trafficking. These illicit gains are laundered through opaque financial circuits. Corruption, including bribery and embezzlement, facilitates and amplifies IFFs, creating an environment of impunity⁶.

7. Fintech and crypto-assets

The rapid rise of fintechs (innovative digital financial service providers) and cryptocurrencies adds a new dimension. While these technologies promote financial inclusion, they are also used for anonymous, almost instant transfers. Regulatory frameworks lag behind innovation, leaving loopholes exploited by illicit actors⁷.

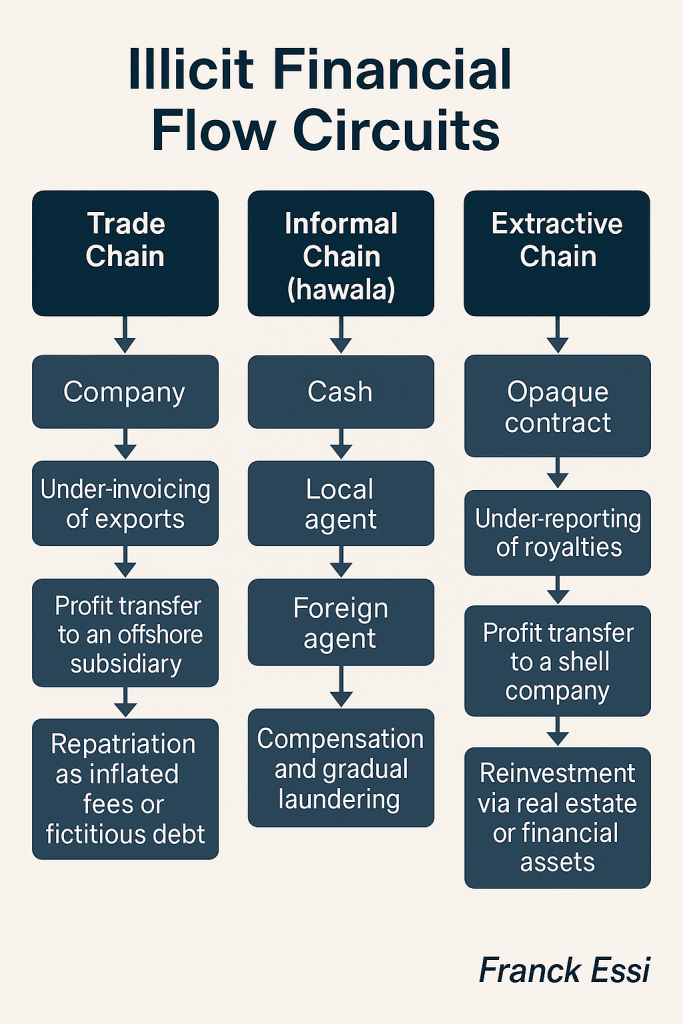

II. Typical Circuits of Illicit Financial Flows

The mechanisms described above combine into sophisticated circuits:

- The trade chain: an exporter under-invoices sales, profits are shifted to an offshore subsidiary, and the funds return disguised as debt repayments or inflated service fees.

- The informal chain: cash is transferred through hawala; intermediaries balance accounts across borders and launder the money gradually.

- The extractive chain: an opaque contract reduces royalties paid to the state; profits are sent to a shell company in a tax haven, then recycled through real estate or financial markets.

These circuits demonstrate that IFFs are both local and global, exploiting institutional weaknesses in Africa while relying on international complicity.

III. Persistent Challenges in the Fight Against IFFs

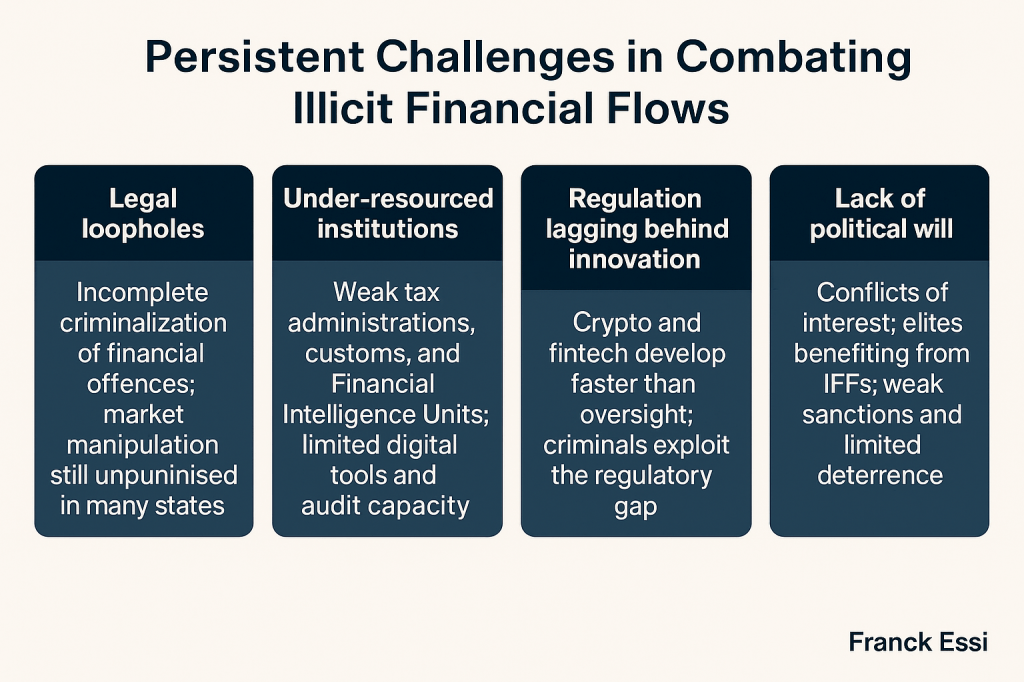

Despite multiple African and international initiatives, several structural challenges remain.

1. Legal loopholes

Many African countries lack comprehensive legislation against financial crimes. For example, in Côte d’Ivoire, certain offenses such as insider trading or market manipulation are not yet criminalized⁸.

2. Under-resourced institutions

Tax administrations, customs agencies, and Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs) lack sufficient trained personnel and digital tools. They struggle to audit multinationals or analyze complex suspicious transactions⁹.

3. Incomplete international cooperation

Only 24 African states effectively apply the OECD’s automatic exchange of tax information. This leaves major blind spots. Furthermore, asset recovery processes remain slow, complex, and rare¹⁰.

4. Regulation lagging behind innovation

Cryptocurrencies and fintech services evolve faster than existing regulations. This gap enables criminals to exploit new technologies with limited oversight¹¹.

5. Lack of political will

In several countries, political and economic elites directly benefit from IFFs. This conflict of interest explains weak law enforcement and the absence of exemplary sanctions. At the same time, growing dependence on debt makes every dollar lost even more harmful to public finances¹².

Closing the Taps to Finance Africa’s Future

Illicit financial flows are not only a matter of lost revenue; they are a structural threat to Africa’s economic sovereignty. They exploit both internal fragilities and the permissiveness of the global financial system.

The fight must go beyond measuring losses: Africa must close the taps by filling legal gaps, strengthening institutions, harmonizing regulations, enforcing transparency on multinationals, and anticipating risks linked to new technologies. Without these measures, billions will continue to vanish, undermining education, healthcare, and the future of the continent.

This article is the second in a series on illicit financial flows in Africa. The next piece will focus on institutional responses and the strategies needed to reverse the trend.

NB: This article was originally published here: https://strategiesconsultingfirm.com/illicit-financial-flows-in-africa-mechanisms-circuits-and-persistent-challenges/

Notes and References

- UNCTAD – Trade Misinvoicing in Africa, 2020.

- OECD – Tax Transparency in Africa 2025.

- Africa24TV – Illicit financial flows: over USD 60 billion lost annually in Africa, 2025.

- Transparency International – Risks of Illicit Financial Flows in Africa, 2024.

- UNECA – Tackling Illicit Financial Flows: Africa’s Path to Reparatory Justice, 2023.

- Interpol & AfDB – Cooperation Against Financial Crime, 2025.

- Carnegie Endowment – Illicit Financial Flows in Africa: Tax and Governance, 2024.

- APA News – Côte d’Ivoire struggles to criminalize certain financial offenses, 2024.

- African Development Bank – Impact of Illicit Flows on Education and Health in Africa, 2024.

- OECD – Automatic Exchange of Information in Africa, 2025.

- UNODC – Organised Crime and Illicit Flows in Africa, 2023.

- Ecomatin – AfDB estimates Cameroon’s losses at XAF 1,000 billion per year, 2025.