By Franck Essi

—

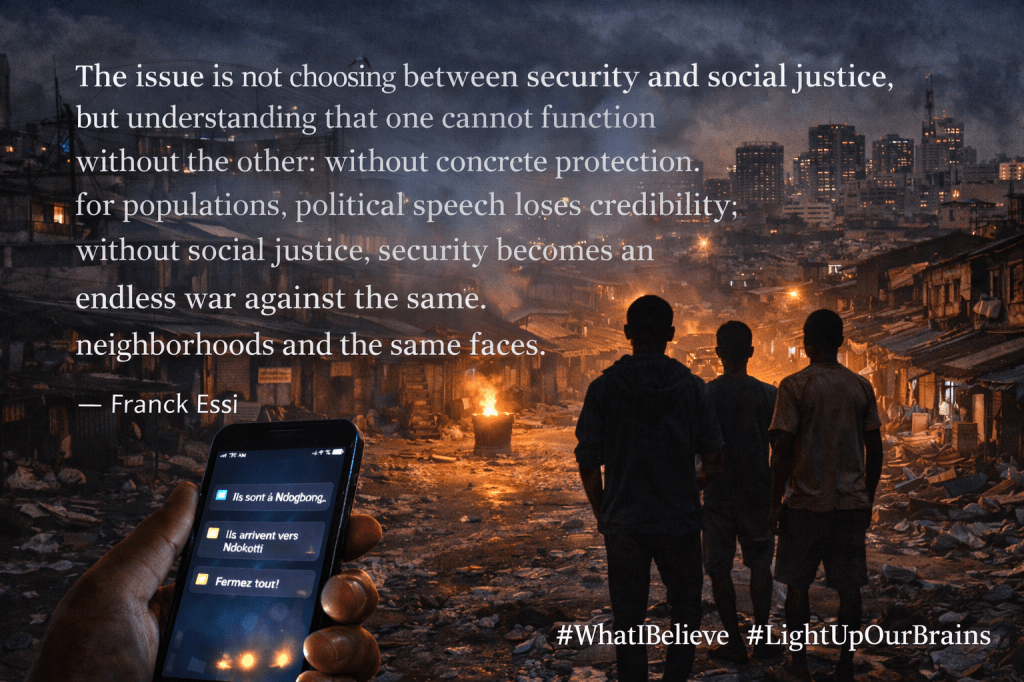

A City Suspended by Its Screens

It is a little past eight o’clock in Douala. Messages follow one another at a dizzying speed.

“They’re in Ndogbong.”

“They’re heading toward Ndokotti.”

“Close everything, they’re moving down toward Deido.”

Metal shutters slam shut. Taxis suddenly change direction. Groups of young people watch streets that have abruptly fallen silent. Within minutes, fear takes hold.

Some images circulate, other rumors spread. Whether true or amplified hardly matters: part of the city slips into an imagination of generalized insecurity. One word appears everywhere: “microbes.” A word that reassures because it seems to explain. A word that simplifies because it avoids thinking.

—

Naming in Order Not to See

Since late November 2022, when the first organized gangs began their raids in Douala’s working-class neighborhoods, the term “microbes” has become the dominant label for these groups of young people armed with machetes and bladed weapons. But the term is not merely descriptive. It is political.

By calling part of its youth “microbes,” a society stops seeing individuals. It transforms a social question into an infection to be eradicated, an urban disease to be “cleaned.”

The word comes from the Brazilian film City of God (2002). It was first adopted in Abidjan after the 2011 post-electoral crisis to describe very young delinquent gangs whose violence echoed that of Brazilian favelas. From there, it spread — like a contagion — to other districts of Abidjan, and later to Douala, imported through media and popular mimicry.

The metaphor is double: cinematic and biological. Like pathogenic microbes, these youths are perceived as small, invisible, yet capable of disproportionate damage. They act in swarms, appear in large numbers (often 20 to 100 individuals), commit their acts, and disappear into the urban fabric.

But a metaphor can become a mental prison. When a human group becomes a disease in the collective imagination, social violence finds moral justification. Dehumanization becomes acceptable.

—

My Thesis: “Microbes” Reveal a Broken Social Pact

We must ask the question differently. What if “microbes” are not a deviation of youth, but the symptom of a state unable to integrate its own demography?

This phenomenon does not emerge in a vacuum. It arises in a society where youth are numerous but invisible, where promises of success are omnipresent yet rarely accessible, where the state is perceived as distant in social matters and brutal in security matters.

Gangs are not born solely from poverty. They are born from a rupture in the symbolic contract between a nation and its youth.

—

Douala: Economic Showcase, Social Fracture

Douala embodies Cameroonian ambivalence. A city of opportunity for some, it is also a city of invisible borders for others. In the same urban space coexist the glass boulevards of Bonanjo or Bonapriso and the densely populated alleys of New Bell, Ndokotti, Bonabéri, or Deido, where access to public services remains fragile.

Out of a population of roughly four million inhabitants, about 1.2 million are between 15 and 34 years old. Among them, nearly 250,000 are in a NEET situation (not in employment, education, or training). Youth unemployment approaches 30%.

Rapid urbanization, saturated peripheral neighborhoods, insufficient social infrastructure: part of the youth grows up in an environment where the visible signs of wealth are everywhere, yet access to that wealth remains out of reach. This visual proximity to inequality creates a specific frustration. The city becomes both promise and constant reminder of exclusion.

This is not only a question of crime. It is a question of how the city is organized.

—

A Youth Searching to Exist

Many of the young people involved share similar trajectories: early school dropout, family breakdown or parental abandonment, absence of professional prospects. The age of the so-called “microbes” ranges from 8 to 27 years old. Most are children living in or roaming the streets, idle, who have formed themselves into gangs.

In a city where the informal economy can no longer absorb demographic growth, some find in gangs a form of identity. The gang becomes a substitute family, a space of recognition, a way of making visible an existence otherwise ignored.

This observation does not justify violence. But it prevents reducing it to mere moral deviance.

—

The Central Role of Drugs and “Sanctuary” Neighborhoods

The “microbe” phenomenon in Douala is intrinsically linked to drug trafficking. The Makéa neighborhood, in the second district, is often cited as the original hub and a trafficking hotspot, from which raids extend to other areas such as Akwa or Bonapriso. Makéa is simultaneously home to many gangs, residence for many of their victims, and the epicenter of Douala’s drug trade.

Attackers often act under the influence of hard drugs (tramadol, “stones”), which give them the courage needed to commit extreme and blind violence. Drugs do not create violence, but they accelerate its mechanics: disinhibition, artificial courage, escalation.

The Boko Haram conflict and the Anglophone crisis, ongoing since 2012 and 2016 respectively, have significantly contributed to the increase in drug trafficking and consumption in Cameroon. This reveals a parallel economy thriving where the official economy fails. In this space, violence becomes a currency — a means to control territory, secure trafficking routes, impose reputation.

—

Violence as Political Language

It would be too easy to consider these youths an exception. Violence is not only a street phenomenon; it also runs through political structures.

In Cameroon, according to some local analysts, the state itself is often seen as the primary source of violence. The non-respect of fundamental rights, the deep entrenchment of corruption in public service, and the constant humiliation of ordinary citizens contribute to building a culture of violence — a “law of the strongest.”

When institutions give the impression that power is conquered through force, when corruption seems more profitable than effort, society learns that might can replace the rule of law. Young people watch. They understand. They quickly learn that success does not come from merit or hard work, but from money or violence.

Young people from poor, vulnerable, and marginalized communities may feel compelled to resort to violence to obtain a share of the “national cake,” because in reality they see few other paths. The street then reproduces, at another scale, logics already visible in the political arena.

—

A State Present to Control, Absent to Accompany

In urban narratives, the state appears in paradoxical form: highly visible during security operations, far less present in social support. Present to repress, absent to prevent.

From time to time, the city witnesses forceful operations: mass arrests, targeted bans on bladed weapons, drug seizures. More than 200 “microbes” were arrested during a single operation in September 2024. Yet such spectacular actions are not always accompanied by comparable efforts in prevention, schooling, vocational training, or community social work.

Cameroon’s police lack sufficient resources — and even more so, training — to deal with urban youth delinquency, often linked to drug use. Failures within the judicial system have led to declining trust in justice and the rise of popular justice. Many offenders caught in the act are perceived to be released only days later.

This perception of impunity fuels the feeling that even when arrested, these youths get away lightly and resume their activities. The absence of structured youth social services, combined with reactive security responses, feeds a spiral where violence becomes an answer to social invisibility.

A nation cannot ask its youth to respect institutions they encounter only as threats.

—

Dehumanization: The Invisible Danger

The word “microbes” has an immediate effect: it simplifies. But it also creates moral distance. It makes acceptable what would otherwise be unacceptable — collective brutality, mob justice, the disappearance of dialogue.

The term conveys the image of a social disease, a harmful infection to be “eradicated” or “cleaned,” which unfortunately contributes to dehumanizing these youths in the eyes of the public and law enforcement. History shows that dehumanization is always a prelude to escalation. A society that stops seeing its young people as citizens ends up treating them as enemies.

—

Repression or Refoundation?

Faced with fear, the security response seems obvious. Yet research on urban gangs shows that repression alone often strengthens group cohesion and radicalizes members. Studies from Abidjan reveal that police operations, without social support, sometimes send young people back into the streets more violent and determined after prison.

Security is necessary. But it must be accompanied by social refoundation. Sustainable approaches involve professional integration programs, local educational and cultural spaces, and community mediation mechanisms capable of rebuilding social bonds and offering pathways out.

Otherwise, each generation will produce its own “microbes.” The issue is not choosing between security and social justice, but understanding that one cannot function without the other: without concrete protection for populations, political speech loses credibility; without social justice, security becomes an endless war against the same neighborhoods and the same faces.

—

What the “Microbes” Really Say About Us

The phenomenon reveals an uncomfortable truth. A society that celebrates its youth once a year — on February 11 — but offers them no horizon the rest of the time eventually turns demographic energy into collective frustration.

Ironically, a country that has turned a date marked by a controversial plebiscite and a heavy legacy of political violence into a national Youth Day still struggles to draw all the necessary political conclusions from that past.

“Microbes” are not a disease of the city. They are a mirror — the mirror of a nation that doubts its capacity to integrate its own youth.

—

When a Nation Calls Its Children “Microbes,” It Speaks About Itself

Let us stop simply calling them “microbes.” Because this word does not only reveal what we think of them — it reveals what we think of ourselves.

It exposes a collective fear, a social fatigue, a difficulty in confronting social fractures, political contradictions, and unfulfilled promises. As long as the response remains mainly lexical and security-driven, the country will avoid the decisive question: what kind of school, urban economy, justice system, and political participation is it willing to offer these young people so that they no longer need to exist through violence?

A nation can choose to see its youth as a threat. Or it can choose to see in this anger a call to rebuild the social pact.

The real question is not how to eradicate “microbes.” The real question is this: what becomes of a nation when its children cease to be its future and become the fear it dreads?

And perhaps the day we stop searching for social infections, we will finally begin to heal our own political wounds.

An abandoned youth becomes an army waiting to be mobilized.

A supported youth becomes a nation made possible.

#WhatIBelieve

#IdeasMatter

#WeHaveTheChoice

#WeHaveThePower

#LightUpOurBrains